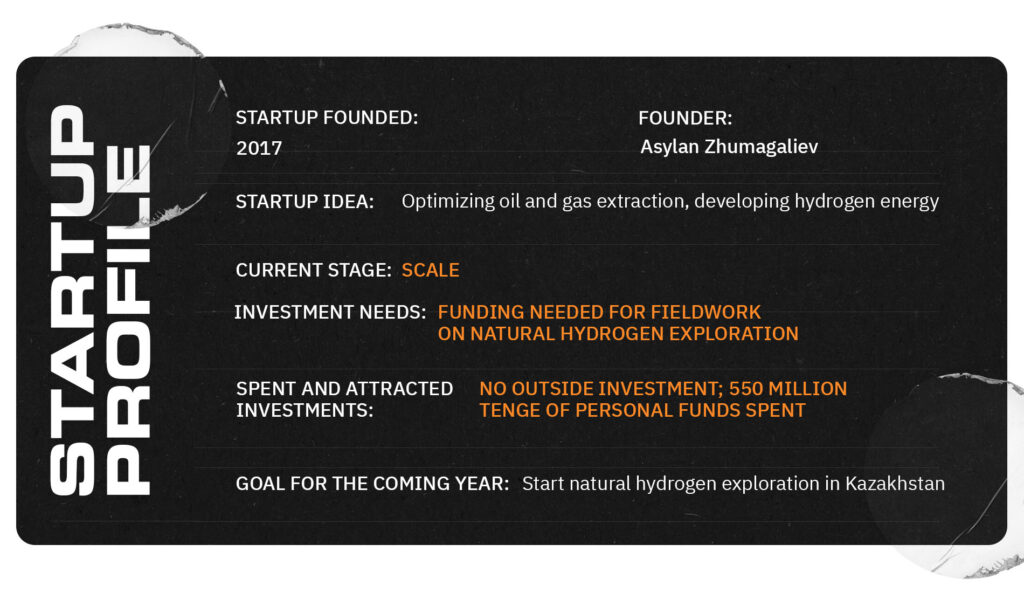

A global revolution in geology and energy could begin in Kazakhstan. This is not a joke or an exaggeration. The analytics system developed by the NeuronOil startup team increases the success rate of drilling and selecting geological and technical measures in the oil and gas sector from 60% to 95%, potentially saving the industry tens of billions of dollars. But even this pales compared to the prospect of a true energy revolution. With enhanced algorithms and formulas, NeuronOil can enable the search for natural hydrogen, which could theoretically become the main energy resource for our civilization for centuries. The ordinary Kazakh lawyer and NeuronOil founder, Asylan Zhumagaliev, shared his business journey, insights into the conservative oil and gas sector, and early international projects with ER10 Media.

Follow Kazakhstan’s Startup Movement in the "100 Startup Stories of Kazakhstan", a collaborative project by ER10 Media and Astana Hub. This initiative highlights the most innovative Kazakh startups, showcasing projects that stand out for their creativity and impact. Among the heroes are Astana Hub residents, as well as creators of other innovative technological products and services. The content is available in Kazakh, Russian, and English.

A Business in Scrap Metal

— Asylan, could you tell us how you got into business? Was it accidental, or had you dreamed of becoming an entrepreneur and worked towards that goal?

— It was probably a coincidence. For a long time, I worked as an employee in both public and private sectors, holding various positions, including company manager. But one day, while living in Zhanaozen, I visited some fields with colleagues and saw huge piles of scrap metal — hundreds of thousands of tons. I wondered why no one was collecting and selling it. It turned out that all this scrap metal was contaminated with radioactive scale. When I asked why it couldn’t be cleaned, I was told it was impossible. Leading institutes had tried for 40 years to develop cleaning methods, but no one succeeded. Legally, you cannot bury radioactive scrap metal; it must be decontaminated first. Only after that can the radioactive material be buried, and the scrap returned to the economic cycle. But there was no cleaning technology, so companies paid hefty environmental fines every year and had come to accept this.

—And you decided you could solve this problem?

— I decided to try. I read literature, studied the problem closely, and even brought the former head of the Chernobyl administration from Ukraine to Kazakhstan, who once managed decontamination efforts. He spent a week studying the issue, examining the dumps, and concluded he couldn’t help — the contamination was too severe. The scrap metal was covered in 3–4 centimeters of radioactive scale that no known cleaning methods could remove.

Then I remembered how my grandmother used to clean pots with scale buildup — she would heat the kettles on a fire, tap them with a spoon, and the scale would fall off. I thought, why not try heating the scrap metal? But how? Building an industrial furnace in the steppe was too expensive. But then I found a solution. During a trip to Surgut, I learned that local oilmen heated pipes with frozen oil using aircraft turbines. I proposed this idea to companies, but for a year and a half, they laughed at me, saying, “For 40 years, the best minds couldn’t solve this, and now you think you can? It won’t work.” But I managed to convince them. They told me, “Here are 10 tons of metal. If you can’t clean it in one shift, don’t come back.” I gathered a turbine, equipment, and workers, set up the operation, and started experiments, heating the scrap. In the end, we managed to do it. This became my first business, launched with borrowed money. Orders poured in, the company grew quickly, with contracts expected to exceed one billion tenge, but some people didn’t like this, and I was eventually forced out of the market. However, I earned enough from this venture to start NeuronOil.

Chance Isn’t Coincidental

— How did the idea for NeuronOil come about? Another stroke of luck?

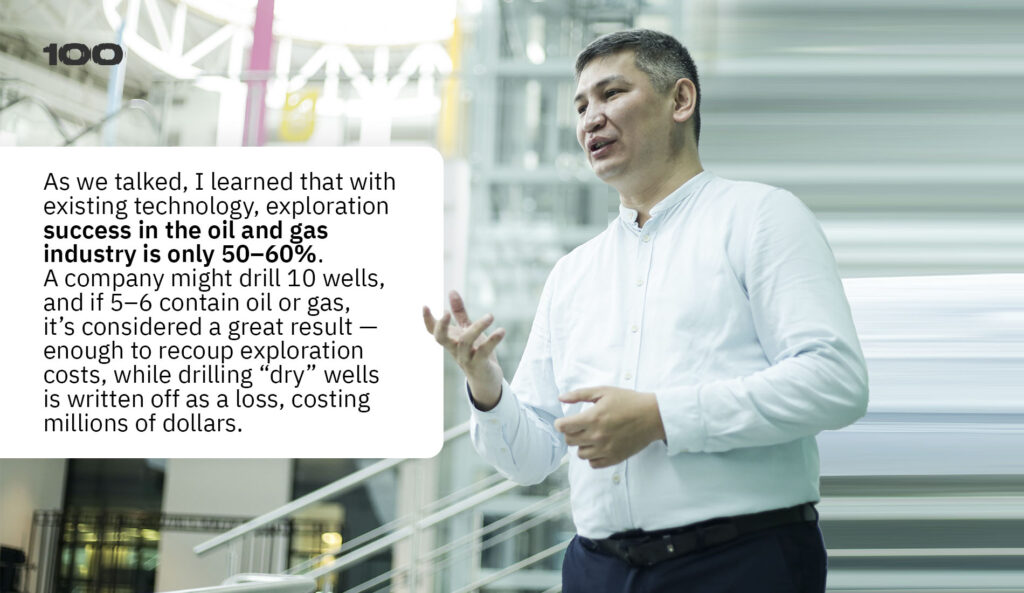

— Yes, the idea came by chance again. In Aktau, I was sitting at a table with a geologist. He received a work call and was visibly upset. I asked him what was wrong, and he replied that an exploratory well turned out dry. As we talked, I learned that with existing technology, exploration success in the oil and gas industry is only 50–60%. A company might drill 10 wells, and if 5–6 contain oil or gas, it’s considered a great result — enough to recoup exploration costs, while drilling “dry” wells is written off as a loss, costing millions of dollars. I argued with the geologist, as it seemed illogical to me. Oil companies have enough money, so why don’t they develop better technology to minimize losses? I learned that everyone had accepted this “gold standard” and no one was trying to change it.

— You thought you could solve this problem?

— Why not. I started researching and reading about the issue. I studied existing technologies and simulators, learning that geologists divide fields into large surface “cubes,” often drilling randomly in such areas. It seemed clear that this technology could be improved. Then I came across an article suggesting that, theoretically, clusters of wells could be used for calculations instead of cubes. Understanding that we could conduct calculations differently pushed me further toward solving the problem. If one technology has reached its peak, a new one is necessary.

— So you decided to look at the problem from a different angle? Even though you don’t have a background in this field?

— As a lawyer, I didn’t understand the formulas and calculations, but through connections, I found a professional geologist and showed him the article on well clusters. He was initially skeptical, but I convinced him to explore other technologies. Two months later, he surprisingly admitted that the new calculation method could work. That’s how NeuronOil started.

Enhancing Exploration Accuracy

— What is the idea behind your product?

— We developed algorithms and formulas based on historical, geological, and other data that increase drilling and selection accuracy for geological and technical measures up to 95%. Considering that each well costs $1 to $15 million to drill, imagine the savings for companies.

Editor’s Note. The global hydrocarbon exploration market is estimated at $60 billion by the end of 2023.

— Why is your technology so precise? What’s the secret?

— The high accuracy comes from our unique calculation unit — instead of a “cube,” we use a well. We can “virtually place” a drill anywhere on the field and calculate the likelihood of hydrocarbons at that specific spot. We can also estimate the percentage of liquids, water, and oil.

— And where do you get the data for these calculations?

— Each subsurface user has such data — daily production reports, monthly operational reports, sample collection, and more. By uploading these into our algorithms, we can predict resource availability at specific locations.

— So, hypothetically, you could arrive in an open field somewhere in the Atyrau region and say, “There are hydrocarbons here?”

— Not quite. Our technology is most effective in already developed fields, known as brownfields. These fields have ample historical data, which significantly aids our analysis. However, we can also work on completely new fields, known as greenfields. We can make predictions, conduct exploratory drilling, and then refine our model as results come in to achieve maximum effectiveness.

Additionally, we optimize water injection systems. Our algorithms help adjust the pumps so they don’t interfere with each other and, in some cases, even work in harmony. As a result, we’ve managed to reduce water cut to 12%. In one well, for example, 98% of the extracted content was water and only 2% was oil. We brought this down to 86% water, meaning that where there was once 20 liters of oil per ton of liquid, there are now 140 liters. This was achieved by reconfiguring the pumps.

— So, your startup is essentially about creating the right algorithms?

— Yes, it’s machine learning. I assembled a team that developed and trained these specialized algorithms.

Growth Is the Only Way Forward

— At what stage is your startup currently?

— We’ve entered the market and are signing contracts. But let me be clear: selling the services of a tech startup is challenging, as our sales cycle is lengthy. Moreover, the oil and gas sector is inherently very conservative. When you approach a company and speak of 95% exploration accuracy, they don’t believe you. It takes a long time to prove it, secure pilot projects, and that all requires time. But we’ve reached our first contracts and self-sufficiency. From here, it’s all growth.

— What projects are you currently working on?

— We’re launching a pilot project in Argentina. It’s a complex project, with a field containing 125 oil-bearing layers — something we’re encountering for the first time. We also have a project in Kazakhstan and are in discussions with two potential clients for pilot launches. We had contacts in Iran, but due to instability, those are currently on hold.

— Do you have competitors?

— Globally, we compete with large oilfield service companies like Schlumberger, Halliburton, and others. Most companies rely on their solutions, which offer about 50-60% success rates.

— So, technically, your product is more advanced?

— Technically, yes.

— Haven’t major companies expressed interest in buying your technology?

— There was a point when I grew tired of the market’s skepticism and even considered selling the technology to Schlumberger, but they declined. They said my product was excellent, but they’re only interested in market share. One manager told me that if we capture 5% of the market in Kazakhstan, they’d come with an offer; if we capture 5% globally, they’d come with an offer we couldn’t refuse.

— Do you have plans to become an international unicorn?

— Absolutely. We’re planning to enter the Argentine market and make a name for ourselves. We’re confident in our technology, and our hydrocarbon exploration business is already operational and profitable. Now it’s time to focus on our new project.

The Hydrogen Future

— I understand that you’re working on an even more promising “green” energy product.

— At present, we’re developing a technology for natural hydrogen exploration. Again, chance played a role here. While working on a pilot project for one company, another team was demonstrating a helium exploration project for oil and gas fields. We became friends with their team and decided to collaborate.

— Why natural hydrogen?

— There’s a well-known case from Mali. In the 1980s, they were drilling for water when a worker approached the well with a cigarette, causing an explosion. The company was frightened and sealed the well. In 2011, a local businessman reopened it and took samples. They found hydrogen levels at 98%. It’s now understood that natural hydrogen deposits exist, although it was previously thought impossible. This is why no one was looking for it. Today, however, startups around the world are searching for natural hydrogen — in the USA, Australia, France, and elsewhere. Even Bill Gates invested $90 million in one project. But they’re all using old technologies like seismic surveys, electrical exploration, geochemistry, etc. I thought that our algorithms, formulas, and helium exploration capabilities could help us find natural hydrogen sources faster and more efficiently.

Editor’s Note. According to the U.S. Geological Survey, the Earth’s subsurface may contain around 5 trillion metric tons of geological hydrogen. Just a few percent of this natural fuel could satisfy the projected global demand for 200 years. More than 40 major companies are now actively searching for geological hydrogen deposits, with their numbers quadrupling over the last three years.

— So, for now, would you say the hydrogen direction is experimental?

— I wouldn’t call it experimental. We’re confident our technology works; we just haven’t tested it in practice yet. Right now, we’re reaching out to Kazakhstan’s Ministry of Science and Higher Education and major universities to jointly conduct field trials and attempt to locate natural hydrogen in Kazakhstan.

— Does your startup need investment?

— We could really use investment for fieldwork on the hydrogen project. Unfortunately, I don’t think there are people in Kazakhstan ready to invest. Conducting field trials on a single site costs around $5 million, just to test and refine the algorithms. So we’re currently trying to secure an agreement with government agencies. There’s understanding and interest, but it’s still unclear if funding will be available.

Will the Hydrogen Revolution in Energy Start in Kazakhstan?

— How would you articulate your startup’s mission?

— Every project I undertake is aimed at not just changing the market but becoming a tool for it. With hydrogen, I don’t just want to change the market; I want to turn it upside down. Natural hydrogen is the cheapest and cleanest energy source, producing only pure water when burned. Today, the production cost of a kilogram of manufactured hydrogen is $7. If obtained from natural sources, the cost would be $1–$1.2. I want the industrial production of hydrogen, which will revolutionize the world’s energy sector, to take place here in Kazakhstan.

— What inspires your business decisions? What books do you read, what films do you watch?

— When I’m interested in a topic, I read all kinds of literature on it, mainly scientific articles. I don’t read books on business or psychology.

— How do you develop your business skills?

— I went through the Google for Startups accelerator at Astana Hub. Before that, I was far from the world of startups. I didn’t even understand how to start a business without using personal funds, relying on investors instead. The accelerator helped me dive into the startup world and learn a lot.

— What sport would you associate with your character?

— That’s hard to say. Probably chess on horseback during kokpar. I dive deep into a subject, think it through, then act swiftly and never stop.

— Does determination help in business?

— Absolutely. When I spent a year and a half requesting radioactive scrap to test my hypothesis, everyone told me, “Stop, no one believes in you.” With NeuronOil, I’ve been forging a path for seven years, investing $1 million in team hiring, algorithm development, and only now reaching commercialization. I could have given up many times along the way. The main challenge in all my projects is the excessive conservatism of the oil and gas market, which is reluctant to embrace new ideas. I’d love to see more trust in the market.